Church and Life

Volume LXXIV, Number 1

Welcome to the February 2026 Issue!

This issue of Church and Life celebrates Winter and, once again, the changing of the seasons—of culture and memorable events of the church and community calendar and of life and milestones in individual experience. We invite you to take time out from the stress of social media or the hectic news cycle and explore with us inspiring and noteworthy stories about the intersections of American and Danish culture. This issue and the next two (April and June) are being launched from Copenhagen, so you might detect a slightly different perspective at work in the pieces included.

We open this February 2026 issue with "It is White Out Here," a poem-turned-song by the Danish poet Steen Steensen Blicher. Written in 1838, Blicher's beautiful poem uses nature imagery to express competing feelings of despair and hope. We believe that Blicher's message is not just for those experiencing the cold of winter; it is for anyone enduring trying times, even times of political and cultural discord. In "Follow Me (a sermon)," Rev. Kelley Hudlow ponders how best to cope with news of recent political violence in the United States. Along with the Craig Loya, the Episcopal Bishop of Minnesota, Hudlow reminds us that the greatest threat we face is the assault being waged on hope and that we must not give in to despair. Edward Broadbridge explains the relationships between Denmark and the European Union (EU), both having been recently in the international spotlight. Broadbridge charts how attitudes in Denmark are changing towards the EU. Dr. Amy Hart tells about moving to Denmark to understand how N.F.S. Grundtvig's educational philosophy prepares students to participate in democratic societies and how it might overlap with the philosophies of American educators like John Dewey. Professor Kristie Chandler also compares American and Scandinavian culture and institutions. She led a study-abroad trip to Scandinavia to learn about the differences (and similarities) between American and Scandinavian Family Policy. She and her students reach enlightening conclusions. Lois Knudsen Lund remembers her time in 1960 as a student at Idrætshøjskolen (The Sports Folk High School) in Jutland near the border with Germany. Maddie Benton interviews Professor Jes Fabricius Møller to learn about his duties as the Historiographer to the Chapter of Royal Orders in Denmark. At the end of Benton's interview, Prof. Møller offers his services to you, the readers of Church and Life. (Read to find out more and take him up on his offer!) Looking to the other side of the globe, Ana Wright talks with Reghu Rama Das about the ideology and practice of Mitraniketan, a Danish folk school in Kerala, India. Reghu maintains that "an educated person should be an active member in the community." And he explains how Mitraniketan helps community members engage. Anita Young sends a reminder to plan to attend Danebod Folk Meeting in Tyler, August 12-23. And we close with a postscript from the editor, Brad Busbee.

In our upcoming April issue of

Church and Life, we will be featuring stories about travel to Denmark or to the USA from Denmark. Please send accounts of surprising discoveries, happy reunions, chance meetings, wild goose chases, or any other memories from your travels. (You can email your stories directly to me at

mbusbee@samford.edu or to

churchandlife1952@gmail.com.)

Church and Life strives to be a forum for stories that speak to shared curiosity and experience. Travel narratives prove particularly interesting in this regard because they are typically about people figuring out what to do in unfamiliar and uncomfortable circumstances and, as a result, learning about others and themselves. Your readers want to hear about what you learned. As

Anita Young says in her announcement about the Danebod Folk Meeting, "Let your voice, questions, and curiosity be heard!"

Let me add another appeal to Anita Young's call to action:

Please give to Church and Life! It is a storied publication, now beginning its 74th year! The media landscape in the 21st century is more crowded with mass media content than ever before, and publications like this one, ones that highlight community, need your financial support more than ever before. Church and Life is free to read, but its production is not free. Its vitality depends on voluntary donations from readers like you.

There are two easy ways to give:

- Click on the “Make a Donation” icon here or when you enter the homepage for Church and Life at churchandlife.com.

- Mail a check (Pay to the order of Church and Life) to:

Andrés Albertsen

1405 19th Ave SE Apt 103

Willmar MN 56201.

A donation of any amount will be tax deductible. Whether you decide to make a gift alone, with a group of friends, with your family, or on behalf of your business or institution, we are happy to work with you. If you would like to sponsor an entire issue, the cost is $ 1,500. Whatever you decide, your donation will be greatly appreciated.

"It is White Out Here" (Det er hvidt herude)

by Steen Steensen Blicher, 1838

It is white out here:

Candlemas* strikes its knot

Exceedingly harsh and hard -

White below, white above,

Thickly powdered trees stand in the forest,

As out in my orchard.

It is quiet out here:

With only a tap on the window pane

The little songbird announces itself.

There are no birds who sing;

Only the finch swings on the branch,

Looking around and tweeting a little.

It is cold out here:

Ravens caw, owls hoot,

Seeking food, seeking shelter.

The crow flaps about with the magpie

High on the ridge of the barn,

Glaring at the tame cattle.

The rooster rises

On a snowdrift; his wings

He claps together clumsily.

He bends his neck proudly and crows -

What monstrous thing does he boast of?

Even if he is predicting thaw!

I long deeply

For spring, but winter grows colder;

Again the wind turns north!

Come southwest, as the frost compels!

Come with your wings of fog!

Come and loosen the bound earth!

*Candlemass (Kyndelmisse), traditionally celebrated on 2 February, is the Church’s blessing of candles and commemoration of the presentation of Jesus at the Temple. It is no longer widely celebrated in Denmark, though some rural parish churches still hold candlelight services that focus on the theme of Jesus as the light of the world.

********

About this poem: In 1838, when Blicher wrote "Det er hvidt herude," Denmark experienced one of its coldest years on record. He was 55, depressed, and suffering from rheumatism. The poem, which was later made a song, is celebrated for its beautiful expression of winter as a dark time of life, but with the immanent hope of spring to come, as the rooster rises and in Blicher's call for the earth to warm again.

Click here for the melody of "Det er hvidt derude." (Take note that you will leave Church and Life if you click the link.)

"Follow Me," a sermon

by the Rev. Kelley Hudlow

“Jesus went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the good news of the kingdom and curing every disease and every sickness among the people.” Matthew 4:23

“For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.” 1 Corinthians 1:18

Yesterday afternoon, I read a reflection by Lutheran pastor Nadia Bolz-Weber. She was replying to a comment, confessing that the person felt overwhelmed by the news. The commenter's question was, “How can I serve the world when the world’s condition is so heavy?”

That is a question that really resonated with me, especially after watching the killing of Alex Pretti, an ICU nurse, by ICE agents in Minneapolis from three angles on my iPhone. News stories, still shots, and opinions flooded my newsfeed. Each post felt heavier than the last.

Nadia responded by reminiscing about the Nintendo game Tetris. The game is simple: rotate the falling blocks to fit them together. When you make a line, the blocks disappear. The game's challenge is that the blocks fall faster and faster. The faster they fall, the harder they are to stack neatly. Eventually, they overwhelm the screen, and you get GAME OVER.

I carried all of that into today's readings when I sat down to edit my sermon. I found myself rearranging and deleting, trying to make it all fit. But what I arrived at was that there was no way to put the news of violence and despair and the gospel together in a way that would make the heaviness go away.

In Matthew’s gospel, Jesus is born into a world where the powerful use violence to terrify and control. In a rage, Herod orders the murder of children. Joseph, Mary, and Jesus flee to Egypt to avoid the slaughter. At this point in the story, Jesus has been acknowledged by the Magi, has escaped a massacre, has been baptized by John, and has overcome the devil’s temptations in the wilderness.

Now, even though John has been arrested, Jesus begins his ministry. He doesn’t go to the expected place – Jerusalem. He doesn’t go to the familiar place – Nazareth.

He goes to a place where people have known darkness and uncertainty–the land of Zebulun and Naphtali. A place on the margins, where Jew and Gentile live next to one another. It is in Capernaum at the Sea of Galilee that God is revealed through Jesus by the calling of disciples. Jesus doesn’t go to the synagogue or to the wealthy neighborhood. He goes to the water to find people who live on the dangerous edge of chaos, who know that to do their work each day requires community—sailing through storms, hauling fish. This is work that can’t be done alone.

Jesus’ message is a familiar one, the words spoken by John the Baptist, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near.” That’s all it took.

These words and the encounter with Jesus led Peter and Andrew, James, and John to immediately leave their work and follow Jesus. We can try to rationalize this call story. Maybe they were already zealots or were really bad at their jobs. Maybe they were mad at their families and ready to run away. Paul’s words are helpful here: “For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.”

They met Jesus and were transformed by the power of God from fishermen into disciples. To the world, they were foolish, but they knew that following Jesus was the only way to be saved. So, what did they follow Jesus to do?

Proclaim the kingdom, certainly. They also followed Jesus into the work of healing.

“Jesus went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the good news of the kingdom and curing every disease and every sickness among the people.”

I think that is still how God is being revealed today through the calling of disciples to proclaim the gospel and to perform the ministry of healing. This healing isn’t just about physical health. Disciples of Jesus are called to heal every sickness among the people. We are called to be agents of healing for the sickness of racism, misogyny, homophobia, and xenophobia—the sickness of hatred, greed, violence, and poverty.

Ultimately, I believed that followers of Jesus are called to be healers of the sickness of despair.

Craig Loya, Bishop of Minnesota, wrote these words yesterday about what is happening there:

The greatest danger we face right now is not the very real threat to our safety. It’s not even the erosion of democracy. The greatest threat we face as a nation is the assault being waged on hope. We must not give in to despair.

Healing despair is heavy work. It is work that cannot be done alone. It is work that takes the whole Body of Christ.

Nadia put it this way, “None of us [is] equipped for all of it—but each of us is equipped for some of it.”

God is revealed not through lone-ranger disciples but through a community, each carrying some bit of the work to heal the world. The work of healing is needed in the powerful places, the expected places, and the places on the margins. The forgotten places where daily life seems to keep going.

For some, it may look like giving our time, skills, and money to organizations that are light bearers and healers in our community.

For others, it may be teaching our young people how to be kind and brave.

For some, it might be creating art, telling stories, writing poetry, so that we don’t forget what is beautiful in the world.

For all of us, it involves prayer. And for some of us, it means advocacy and protest. None of us can do it all, but all of us can do something. Carry what you can. Give what you are able.

Jesus says, “Follow me.”

Follow me so that you are never alone.

Follow me to light and life and hope.

Amen.

The Rev. Kelley Hudlow is the Instructor of Preaching at Bexley Seabury Seminary. She also serves as an associate rector at All Saints Episcopal Church in Homewood, Alabama. She lives in Birmingham, Alabama, with her spouse, Dr. Shanti Weiland, a poet and English professor; Brother Juniper, a ginger corgi; and Julien, a ginger cat. This sermon was first delivered on January 11, 2026, at All Saints Episcopal Church in Homewood, Alabama.

Dateline Denmark

By Edward Broadbridge

Denmark and the EU

After the First World War (1914-18) the League of Nations was set up in 1920 to promote international cooperation, peace, and security. It failed to prevent the Second World War and was dissolved in 1946. In its place came the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), established in 1949 by 12 nations, including Denmark, and now an alliance of 32 European countries and the USA.

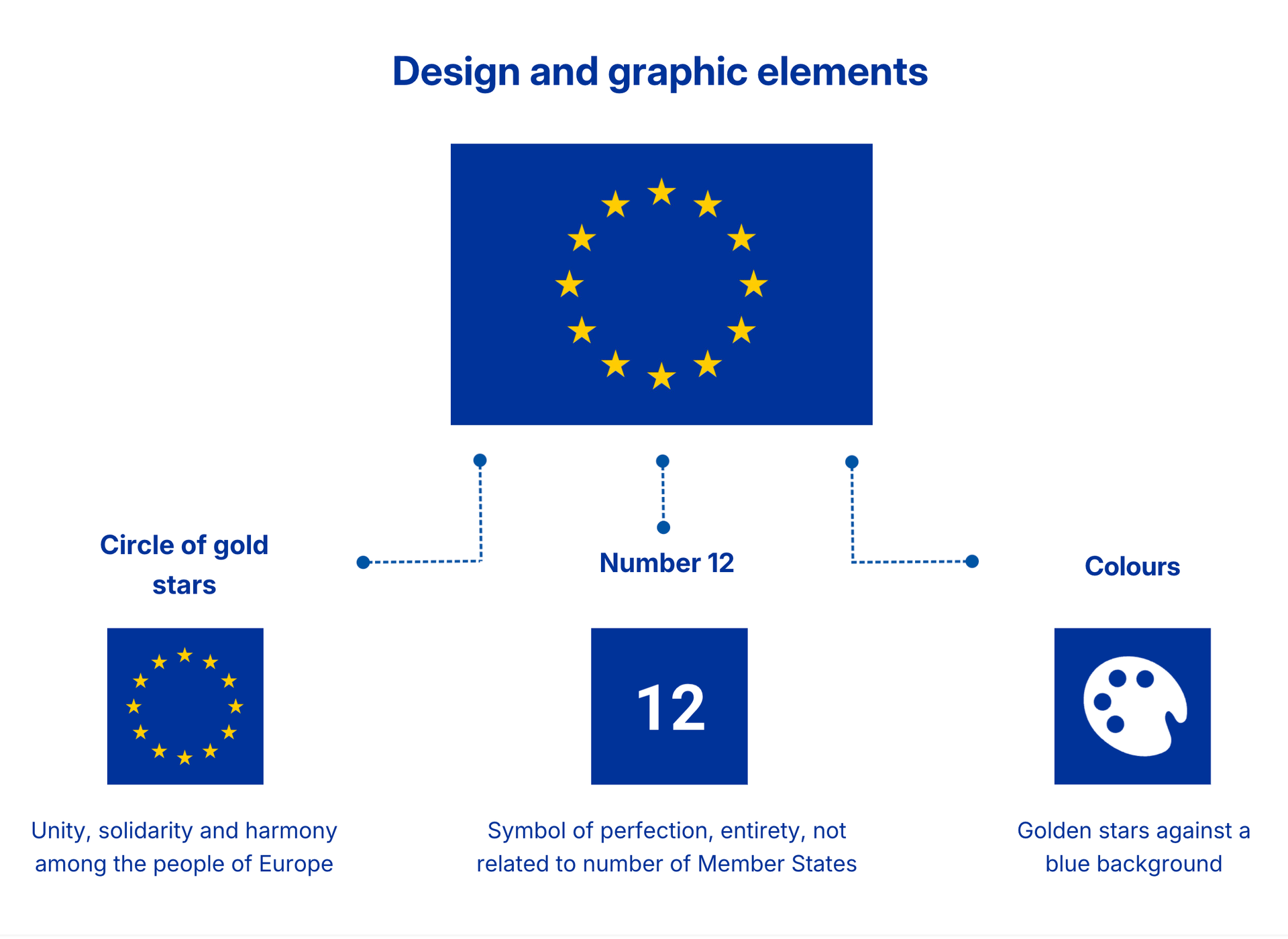

A further attempt to avoid conflict in Europe came about in 1951 when the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was set up by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany. In 1957 this was replaced by the European Economic Community (EEC), which was renamed the European Community (EC) in 1993 and then became the European Union (EU) in 2009, an organization of 27 countries, including Denmark.

Along with the UK and Ireland, Denmark joined the EU in 1973, though it opted out of the Euro currency when it was introduced in 1999 and retained the Danish krone (crown). With a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $76,581 per capita, well above the EU average ($49,880), Denmark's GDP ranks 4th in the EU, after those of Luxembourg, Ireland, and The Netherlands. The USA figure is $88,000, Russia’s is $17,500, and China’s is $13,000. Denmark accounts for 2.2% of the EU's total GDP.

Since joining the EU in 1973, Denmark has blown cold and hot over the EU rather than hot and cold. It has opted out of the Eurozone (EMU), Justice and Home Affairs (JHA), and EU citizenship, all of which ensure that Danish currency, judicial, and immigration policies remain independent. But after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Denmark opted into the defense agreement. In 1972 a political party was formed specifically to oppose entry into the EU. But the People's Movement against the EU, a far-left political association which was represented in the European Parliament from 1979 until 2019, lost its single seat in the European Parliament election. The main opposition to the EU nowadays is the Danish People’s Party, but it is fighting a losing battle. It argues that the EU undermines national sovereignty, acts as an elite organization with limited transparency, and imposes too many regulations on economic policies. However, a Eurobarometer (Winter 2025) survey shows that 66%of Danes believe that “over the next few years” the role of the EU will become “more important” (EU average is 44%). Moreover, a full 82% of Danes expect that in the future the role of the EU “to protect European citizens against global crises and security risks” should be “more important” (EU average is 66%). When asked in greater detail about the most important policy areas for the EU, Danes identify “Defense and security” (52%), “Energy independence, resources and infrastructures” (36%), and “Competitiveness, economy and industry” (30%) as a top three.

Perched geographically as the northernmost EU country, Denmark has only slowly felt the pull from the south. When it last held the 6-month presidency of the EU in 2012, there was not much interest or enthusiasm in the country, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine has galvanized support for the EU. Denmark again held the 6-month presidency of the EU in the last half of 2025. Speaking in October 2025, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen declared that “for many Danes, European co-operation has never really been a darling,” but “the old world is no longer. We are in new times.” She was referring to Presidents Trump, Putin, and Xi--all of them opponents of the EU.

Moving to the Home of Grundtvig: My transition from California to Copenhagen in Pursuit of Grundtvigian Knowledge

by Amy Hart

In August, my husband and I packed our airline-approved bags, placed our dog in his carry-on sized carrier, and left our home in California to move to Copenhagen. My husband had just been offered a position as a visiting researcher at Aalborg University (based at their Copenhagen campus), and I took the opportunity to pursue my research interest in N.F.S. Grundtvig and his educational model.

My interest in Grundtvig developed during my time working as a program manager at the Office of Public Scholarship and Engagement at the University of California, Davis, where I was researching the history of social and educational reform in the U.S. and came across the name Grundvig in the context of the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. I was surprised that I had never learned about this influential reformer from Danish history, whose educational reforms and social vision seemed to align well with those of American social reformers from the early twentieth century. My Ph.D. is in History, and my dissertation focused on 19th-century female social reformers, including leaders of the women’s rights, abolition, and common (or public) school movements in the United States. In recent years, my research has become more focused on educational reform history, and I now have the opportunity to pursue my interest in Grundtvig’s particular approach to educational reform from his home country for at least the next year (and hopefully longer, if all goes to plan). This is the story of my transition to Denmark, and the incredibly widespread influence of Grundtvig that I have noticed in everyday experiences here.

We arrived in Copenhagen in early August—a wonderful time to explore Denmark, bask in the beautiful Danish summer, and build some memories of the warm sun and long days to draw upon for comfort during the dark days of winter. Shortly after my arrival, I started meeting regularly with Grundtvig expert, Anders Holm. A professor of church history at the University of Copenhagen, Anders is widely acclaimed for his knowledge and publications on Grundtvig, and has even published a book (which has been translated into English) introducing readers to Grundtvig and describing Grundtvig’s international influence. Anders kindly agreed to be my supervisor for a proposed Marie Curie postdoctoral grant, a prestigious fellowship based in Europe that provides researchers the opportunity to pursue research on a topic of their choice for two years at a European host institution.

We proposed a project that will focus on tracing the similarities in the educational reform message of Grundtvig and that of American Progressive-era education reformers, including John Dewey, Jane Addams, and Francis W. Parker. Like Grundtvig, these American reformers advocated for a holistic educational model that would prepare students to participate in democratic society, instead of focusing on narrow disciplinary study and rote memorization.

While Grundtvig’s vision of democratic, holistic education has been examined within the Danish context, its potential connections to American educational reform have received little direct scholarly attention. This project would use new AI-assisted text transcription tools to analyze Grundtvig’s writings alongside those of American Progressive-era reformers. These AI-assisted tools have made Grundtvig’s writings (and handwriting) more accessible to scholars by “learning” to read his written papers and turning them into text-searchable digital documents. I hope to learn to utilize AI transcription technology as part of the project, in addition to gleaning insights on the potential impact of Grundtvigian educational ideas across transatlantic contexts.

The application process for Marie Curie fellowships is notoriously long and tedious, and I appreciate Anders’s patience and willingness to dedicate so much time last summer and fall to navigating the application forms with me. As part of developing the application, Anders lent me books and suggested relevant people I could reach out to in the effort to learn more about Grundtvig. Of course, learning about Grundtvig must involve more than just reading about him, but also experiencing his continued legacy in Denmark as well. So, I started exploring Copenhagen, with an eye to learning more about Grundtvig in the process.

I joined a badminton association soon after arrival in Denmark. Badminton was a sport I had loved playing in gym class in high school, but I rarely got the opportunity to play the sport outside of that limited period, as it just isn’t well-known in the United States. Luckily, it is one of the most popular sports in Denmark, and the Danes are world champions in it—Denmark frequently medals in this sport in the Olympics. This association has been a wonderful way to get to know people from my neighborhood, and has motivated me to stay active, even as the days grow shorter. The prevalence of associations in Denmark is a legacy of Grundtvig and is arguably one of the ways Danes have become such a trusting, peaceful nation—the shared activities they regularly participate in create opportunities for dialogue and connection, something sorely lacking today in the United States. In an increasingly online and self-isolating world, Denmark’s strong history of associations shelters its citizens from some of the social consequences of our anti-social moment. In early September, the Grundtvig Forum, a Copenhagen-based organization dedicated to honoring the history and legacy of Grundtvig, held their annual festival of learning and reflection, called Himmelblå (blue sky). This festival included almost a week of singing, lectures by scholars and church leaders, tours of historic sites relevant to Grundtvig, and more singing. All events were held in Danish, and my Danish skills are still very limited, so I attempted to use Google Translate to provide a real-time translation of the speakers, and while I only partially caught the meaning, the feeling still came through. At the beginning of each session, we sang Grundtvig’s hymns as group. Hymnals were provided, though it was clear that many attendees knew most of the songs by heart.

Community singing is a big part of life in Denmark, and it’s not just an activity for children! My local “kulturhus,” or community center, holds weekly community singing sessions where people can come together to sing familiar Danish songs, typically about nature, friendship, and the finicky weather. I have experienced the Danes’ love of singing together in various contexts now, and it is clearly another legacy of Grundtvig, the prolific hymn writer.

The “lectures” I attended at the Himmelblå festival were much more conversational than the traditional presentations I am used to attending in the U.S.—a very Grundtvigian approach to the speaking model. The talks varied in topic: One that I attended featured a pastor, speaking to the past and future of the Danish Church. Another discussed happiness in Denmark (which has repeatedly been named the happiest country in the world). The speaker emphasized the importance of community to creating happiness—and credited the prevalence of associations or clubs in Denmark with orchestrating community here.

As the winter approaches, I am trying to appreciate the positives of this cozy (or “hyggelig”) season. I’ll try to do as the Danes do: Create opportunities to get together with friends, preferably with candlelight, coffee, and sweets. I’ll continue participating in my association (thankfully badminton is an indoor sport!) and I’ll invest in some warm clothing that allows me to spend time outside each day (a dog is a great motivator for this). As I await news on the results of the Marie Curie grant application with crossed fingers, I can now take the time to appreciate Grundtvig’s influence in the daily life I live in Denmark.

Exploring Family Policy Abroad: A Journey through Scandinavia

by Kristie Chandler

In May 2025, eleven students from Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama, and my husband and I landed in Copenhagen. Of course, it was not as simple as all of us beginning our journey from the same location, on the same plane, and arriving at the same time. Such trips rarely are. Instead, almost every one of us arrived in Copenhagen via a different path, complicated by delayed planes and missed flights. Eventually, however, all of us arrived at the same destination. And what a beautiful destination it was! We stayed in Denmark the first eleven days of our trip. Then we travelled to Sweden for the next six days.

The purpose of our trip was to examine the intersection of history, faith, law, policy, and culture of Denmark and Sweden by comparing family policy in those countries with those in the United States. Naturally, the experience gave us opportunities to reflect on the cultural values and priorities that support different approaches. Along the way, we were all encouraged to think deeply about how cultural perspectives and policy decisions can work together to influence the well-being of families.

But I should pause to define what I mean by the phrase "Family Policy." Karen Bogenschneider, author of Family Policy Matters (2024), defines Family Policy as a subset of public and social policy. It aims to protect, promote, and strengthen families by addressing at least one of the following five functions that families perform:

- Family Formation (marriage, divorce, and bearing or adopting children)

- Partner Relationships (commitment and stability of the partner relationship)

- Economic Support (financially providing for family members’ needs)

- Childrearing (educating, feeding, socializing, protecting the health and safety of children)

- Caregiving (assistance for children and adults with disabilities, elderly, and frail/ill.)

I have been teaching Family Policy courses for more than 10 years; twice I took students to Washington, DC, and once to London, where we explored the five functions above. While these were unique and valuable experiences, I knew that Denmark and Sweden consistently rank near or at the top of global lists for Family Policy, as well as for social and family well-being. Both countries have long been recognized as pioneers in progressive family policies, with comprehensive social welfare programs, generous parental leave policies, and accessible childcare services.

I was eager to see first-hand how these policies foster family-friendly environments, work-life balance, gender equality, and overall well-being. I knew that my students would gain valuable insights into the practical implementation and impact of social welfare measures. But the best reasons to visit Denmark and Sweden for my course is that these countries radically contrast with the United States in how they implement Family Policy.

The United States has a diverse population and varied social and economic landscape, while Scandinavia has more homogeneous societies and similar economic structures. Students would be forced to consider how different cultural, economic, religious, and political contexts influence family policy outcomes. It did not take long for the students to see first-hand why Denmark consistently out-ranks many countries. They saw Danish Family Policy in practice, manifested, for example, in subsidized childcare, extensive parental leave, and support for work flexibility. They also began to understand why Denmark continually ranks as one of the happiest countries in the world. Trust in social institutions and government, work-life balance, and quality childcare are frequently cited as reasons for their sense of well-being. They also saw the Scandinavian commitment to human rights, particularly in how Danish and Swedish legal systems quickly adapt to societal changes. Emily Armstrong, one of the students in the course, wrote, “The experience helped me understand that family policy is about more than legislation, it's about the values that guide how societies care for people who need the most.” Insightful observations like that are gratifying to a professor.

While the main goal for our trip was to compare family law and public policy, I also hoped students could experience the rich historical and religious landscapes of Denmark and Sweden. I wanted them to see museums, attend community events, and meet officials in educational, government, and social service agencies. I wanted them to get a feel for the Danish idea of "hygge" and the Swedish tradition of "fika," which no doubt influence each country’s approach to family and community life. Students seemed to tune into this influence. From everyday encounters, students could see that garbage workers are valued as highly as scientists, and childcare workers as highly as engineers. Work–life balance and contributions to society take precedence over income or status. We heard what it means to raise a “Viking child.” And again and again, we encountered a guiding principle: those with the broadest shoulders should carry the heavier load. Or, as Scripture puts it, “From everyone who has been given much, much will be demanded” (Luke 12:48). These values were clearly reflected in the family policies we examined.

But what struck me personally the most was the difference between universal access in Denmark and Sweden and the conditional, means‑tested approach in the United States. That distinction may explain why trust in government is so much higher in Denmark (around 70%) than it is in the U.S. (around 25%). In the U.S., programs like SNAP, Medicaid, and TANF are available only to those who meet strict income and work criteria. Because these benefits are not universal, they can create feelings of stigma, mistrust, or unfairness among those who receive them—and among those who do not.

And at the end of the course, we compiled the following list of four comprehensive takeaways about Family Policy in Scandinavia:

- The Reformation shifted the responsibility for caring for the poor from the Catholic Church to the state and the community.

- Danish culture came to value the dignity of work and personal responsibility.

- Poverty began to be understood as a social issue rather than a moral or spiritual failing.

- Religion, morality, and governance became intertwined in a way that framed welfare as a civic responsibility—the idea that the state should care for its citizens.

These elements form the religious, moral, and faith-based foundation of the Danish "Welfare State," which Professor Anders Holm, one of our gracious hosts in Copenhagen, defined as one in which “the government protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of all its citizens. To do this, through taxation, funds are transferred to services like healthcare and education as well as to individuals.”

Idrætshøjskolen 1960

by Lois Knudsen Lund

In 1960 at age 19 and after one year at Grand View College, I decided to join my parents (Ellen and Joe Knudsen) and my sister Sonja to Heidelberg, Germany, for the fall semester of my sophomore year. My father was on sabbatical leave, and I was to enroll in the university to further my study of German. I had taken several years of German in high school and one at Grand View. However, it soon be clear that I was out of my league, and I began to skip classes. I finally confessed to my parents, and we decided I should spend the rest of my time at a Folk School in Denmark.

We had lived in Denmark for six months when I was ten, and I knew some basic Danish. I had already mastered “rødgrød med fløde” (red pudding with whipping cream) and other important phrases, so I thought I could survive immersed in a Danish environment. My father was friends with the forstander at Idrætshøjskolen (Sports Folk High School) in Sønderborg, so I was allowed to enroll late for the fall term. The focus of my session was on gymnastics, primarily training adults to teach pre-school children. The gymnasium had first-class equipment and a swimming pool half the length of an Olympic-sized pool. Academics were part of the curriculum, but not the main emphasis, so this was a good fit for me.

We were three American and one Canadian young women and two young men from Flensburg, Germany, that made up the foreign student group. We participated with the Danish students in all classes but one, Basic Danish Language. One day we were discussing Australia, and I decided to practice my Danish and share my knowledge of some history. I proceeded to explain that in the mid-1800s, the English introduced rabbits for hunting. They soon multiplied and became a major agricultural and environmental pest. I said that the kinesisk (Chinese), not kanin (rabbit), were running wild in Australia and the government had issued hunting and poisoning methods to irradicate them. Needless to say, it was a while before I volunteered again in class.

On the evening of Thanksgiving, the six of us foreign students decided to ride our bikes to town and have a beer to celebrate the holiday. The next day the forstander announced over the loudspeaker that any students who recently had drunk alcohol should report to the auditorium.

Sundays were open house, and students could visit each other in their rooms in the afternoon. Apparently, some of the students had been drinking during these visits, and the staff thought this had become a problem. The six of us sheepishly went to the meeting. After a lecture on drinking, the forstander asked us what we had done. We explained that we had had one beer in town the previous night. Trying not to smile or laugh, he dismissed us with no penalties.

Our days were filled with basic classes on physiology and the importance of healthy bodies; on gymnastics, mostly floor exercises; and swimming and diving. The lectures were mostly above my understanding of Danish, the diving off high boards daunting, and the gymnastics mostly tolerable. Despite these challenges, I much enjoyed learning new skills. We sang every day, and I remembered the songs from my time as a child visiting relatives and ending the evening in song. Lunch time was particularly important for me. The forstander would stand in the middle of the dining room and flip letters to us, some sailing the length of the room. I eagerly awaited letters from my friends at Grand View, especially Gordon Lund who was my boyfriend and would become my husband.

Idræts is in Sønderborg in Jutland on the border of Germany near Lillebælt, a strait between the island of Funen and Jutland. We took many walks along the shore, and one time I suggested we sing “The Danish Hiking Song,” a song my father had translated. My friends looked puzzled, so I sang the two verses. They had never heard of it, and once again I felt naïve and out of touch with the Danish culture as I thought I knew.

I left the school at the Christmas break. It was time for me to return to Grand View and spring semester. But, first, I had an invitation to join a Norwegian friend for her school’s New Years’ weekend holiday of skiing. I took a taxi to the ferry at Frederikshavn where I would sail to Oslo, Norway. When I left the cab, the driver asked if I was from Sweden. I was a Scandinavian in his eyes, albeit Swedish, not an American trying to speak the language. This was my crowning moment. I could go home proud of my experiences and accomplishments.

An Interview with Jes Fabricius Møller, Denmark’s Historiographer to the Chapter of the Royal Orders

by Maddie Benton

For this February 2026 issue of Church and Life, I spoke with Jes Fabricius Møller who serves as Denmark’s Historiographer to the Chapter of the Royal Orders. Møller spoke with me about his work and the way it preserves Danish history.

Perhaps, like me, you have never heard of a "Historiographer to the Chapter of the Royal Orders." Møller noted that the position was created in 1808, and he is the tenth historiographer to hold the position. Møller explained that, despite common misconceptions, “being the house historian does not imply that he writes the history of the present monarchy.”

Instead, Møller serves as a “historical consultant to the royal house.” This is a role that implies maintaining the institutional memory. “The royal house is the oldest institution in many ways in Denmark and has to be reinterpreted by every generation,” he says.

I asked Møller what the most challenging part of his job was, and he explained that his role requires “a lot of discretion.” Møller also serves as a professor at the University of Copenhagen, and he noted how important it is for him to “maintain integrity and independence as an academic.”

If doing research on the monarchy, he does not deal with current issues so that he has “the full freedom to write whatever he considers the truth about that matter.” (One of the best parts of his job, he noted, is getting invited to the royal parties. He even has his own historiographer uniform!)

Møller also described how he “curates” an “archive . . . of autobiographies.” Autobiographies play a central role in Denmark because, when people receive an award in Denmark, they “hand in their autobiography in order to document that they actually deserve being decorated.” Møller is in charge of managing over 40,000 of these autobiographies, which tell stories of people from all walks of life.

When I asked Møller about the significance to present and future generations of the position of Historiographer, he mentioned the autobiographies. They play an important role in contemporary genealogical studies, and he “can provide many people with the autobiography of their grandfathers,” allowing present-day Danes a glimpse into their histories. The autobiographies Møller is curating now will “be of great benefit to future genealogists.”

After I finished interviewing Møller, he had a question for me. He asked whyChurch and Life wanted to interview him. When I explained that the publication seeks to connect readers with Danish culture, Møller mentioned that I should include his email address in the article, and that readers should reach out to him if they have Danish ancestors who have received a Danish medal or order.

Here is Møller’s email if you are interested: jfm@kongehuset.dk.

My conversation with Historiographer to the Chapter of the Royal Orders Jes Møller offered an opportunity to explore how Denmark seeks to honor its past and preserve its present. In many ways we aim to do the same cultural work as Møller withChurch and Life, connecting our readers to Danish history and culture.

Mitraniketan: The Power of Folk Education

by Ana Wright

Did you know that there is a flourishing Danish folk school in South India?

I recently spoke to Dr. Reghu Rama Das, the principle of the Mitraniketan People’s College (MPC) in Kerala. The MPC was founded in 1996 in cooperation with the Association of Danish Folk Schools, and it is part of a larger nonprofit organization called Mitraniketan that includes a primary school, an agricultural center, a technology center, and a women's development program. Reghu was excited to explain how the MPC is using the folk school education model in conjunction with these other projects not only to enrich the lives of individuals, but also to transform the entire community.

In Reghu’s words, the mission of the MPC is to “promote rural leadership through education programs; To build leaders so that they will become active citizens in the community.” Many of the students who attend the school are from rural backgrounds, and the programs at Mitraniketan give them access to employment opportunities they would not otherwise have. This allows them both to improve their own living conditions and to help develop their local communities. As Reghu put it, “education is not for the individual’s development alone. It is not for the family’s development alone. It is for the community. An educated person should be an active member in the community.”

Mitraniketan also promotes cultural exchange by inviting volunteers from all over the world. At times, Reghu said, they have hosted as many as 40 volunteers at once, and these volunteers teach English, art, sports, and anything else that may be needed.

The MPC is an inspiring testament to the power of folk education to transform society. By integrating learning, community, cultural exchange, and entrepreneurial, agricultural, and technological development, this rural school in India is truly making the world a better place.

Mitraniketan as a whole truly embodies the principle of “education for life.” In fact, Reghu said that his favorite thing about Mitraniketan is how all the different programs work together to serve the local community holistically. “Along with education,” he explained, “we are integrating livelihood skills, life skills, and related activities, and integration is an important part of this system.” For example, alongside the folk school where young people live and study together, the Women’s Empowerment program trains adult women in entrepreneurship, helping them to utilize the natural resources available to them to create and sell products, and the technology center helps to improve productivity by developing technologies suited to local projects. By implementing programs like these, Mitraniketan helps to meet the specific needs of those it serves.

Learning and Engagement at the Danebod Folk Meeting

by Anita Young

This is a reminder to mark your calendar for the Danebod Folk Meeting in Tyler! New friends are made, old friends reunited. Teachers and students learn from each other.

These are some of the foundational tenets of the Danish folk school tradition and the annual Danebod Folk Meeting. At the 2026 Folk Meeting, August 19-23, professionals and participants will come together for three and a half days of mutual hands-on learning.

This is your opportunity not only to hear from experts on topics such as economics, political campaigns, and new methods for learning with Legos, but also to let your voice, questions, and curiosity be heard! All events, from lectures to leisure, are designed for maximum interaction and engagement.

Don’t let another season go by. Mark your calendars today, and join us in Tyler for three days of lively discussions and experiential learning!

Contact me, Anita Young, for information: 612-860-8070.

Postscript

by Brad Busbee

It is an interesting time to be an American living in Denmark.

In January, my wife, son, and I travelled to a small village called Veddelev, outside Denmark’s cathedral city of Roskilde, for a six-month sabbatical. A few days each week, I head to the Royal Library in Copenhagen or to my office at Copenhagen University, where I am part of a team transcribing 90,000 pages of N.S.F. Grundtvig’s unpublished handwritten texts. Every day, my wife, Kathleen, sets out to the market, makes fresh bread, meets with friends, and exercises or walks along the fjord. And every day, my son, Elias, makes his way through the snow—Denmark has seen unusually heavy snow this year—to Hedegårdenes Skole in Roskilde where he’s learning Danish along with other students newly-arrived in Denmark, young people from places like the Democratic Republic of Congo, India, Poland, Sweden, Turkey, and Ukraine. Three days a week, he plays soccer with boys in his local soccer club, Himmelev-Veddelev Boldklub.

We are fortunate to be part of Danish culture and to have close friends who make our time enjoyable. Denmark is safe, clean, and peaceful. The Danes are content, well-educated and healthy, law-abiding and progressive. Our neighbors are kind, courteous, and helpful, readily offering a snow shovel or bus information or observations how we should be sorting our recycling / garbage (which is a very complicated process).

Yet there’s no denying the initial unspoken tension when we meet people for the first time. It’s clear they want to ask about what is happening in the USA. But they don’t at first. Later, once we become better acquainted, they take the leap with a question possibly less graceful than they had intended, something like “What do you think of your president?” The tone of the question reveals subtexts of concern, anxiety, even fear about the American president’s stated intention to take Greenland by force. Recently, after Trump backed down from his threats of invasion and in the aftermath the ICE killings of innocent citizens in Minnesota, the deeper subtexts have shifted to disbelief and sadness. They are wondering what's happened to a country they love and admire. In the week leading up to publication of this issue of Church and Life, with the open racism of Trump’s social media posts in the news, the tone seems to have shifted again, this time to disgust. How could Americans let this happen? Aren’t they going to do something about it?

Discussions about America are usually respectful, though sometimes awkward or unsatisfying because we, the supposed experts, don't know how to respond or don't have answers. At a dinner party in mid-January, a refined gentleman asked if the citizens of the US were preparing for war. During a post-practice “fællesspisning” (team dinner), Elias’s soccer coach asked why the US was turning its back on NATO. He had heard about the harsh speech Trump gave at Davos. Last week, Kathleen visited the World Health Organization (W.H.O.) to lunch with a friend who works there. (The US officially completed its withdrawal from the W.H.O. on January 23rd.) She had an elaborate conversation with a security guard, who said that world-wide, it’s the less fortunate folks who are suffering this radical change in American foreign policy. He’s right, of course, and his dialogue with Kathleen was friendly and thoughtful. Danes are generally well-informed about international politics, and we find that they are willing to engage for better understanding.

But a mixture of confusion, sadness, and disappointment was evident on January 23rd at the 75th anniversary celebration of Fulbright Denmark. Speakers included an American expatriate Greenland researcher, the Danish Minister of Education, Christina Egelund, and the newly appointed American Ambassador to Denmark, Ken Howery. A crowd of about 150 people was gathered in a late-medieval city center building of Copenhagen University, in a gorgeous room with ornately painted walls and ceiling. Mostly Danes were present, along with a few American Fulbright Fellows, current and past. (As a 2003-04 Fulbrighter, I attended with my family, and my colleague Anders Holm, who was awarded a fellowship to the USA in 2016, brought his wife, Marie.)

In his presentation, the Greenland researcher didn’t mention angst surrounding his research; instead, he talked about how he stood at the nexus of American, Danish, and Greenlandic cultures and how he adored all three. Egelund, however, directly addressed Danish and American political tensions. “There’s never been a time when international partnerships between two nations, like the Fulbright Programs, have been more important,” she said. (She’s right, too, of course.) Egelund’s speech was greeted with hearty applause. Howey did not mention Greenland or US-Danish political tensions. He had just arrived in his position and had not yet, at that point, been officially acknowledged by the Danish King or the Danish government. His silence on those issues was understandable, and he received polite applause. The reception that followed was lively and friendly, and the event was beautifully done, but an anxious fog hung over the gathering.

I offer these observations about how everyday Danish people are responding to events in the USA because they suggest to me that a ground-level shift is underway. It seems that, at least in Denmark, the good will the USA has enjoyed for so long is quickly waning. Here's a telling example: My research assistant showed me an app on her phone that she uses when shopping. It helps her identify goods owned or made in the USA or by American companies so that she can avoid them. She told me that most Danish university students use the app. Here's another example: The morning radio news reported matter-of-factly on the racist social media post about the Obamas. The information was shared as notably awful but unsurprising. And it's normal for radio hosts to frame Danish-US relations as a series of David-and-Goliath scenarios: Fist-bumps after Lars Løkke Rasmussen, Denmark's chief foreign ambassador, met with J.D. Vance and Marco Rubio, laughter in parliament at ridiculous demands for a Nobel Prize, and so on.

So what’s to be done?

Public opinion takes time to change, and I expect that long-binding affinities between the people of Denmark and the people of the USA will eventually transcend the unhappy politics of the current administration. This year, while fewer Danes are choosing to travel to the USA, more American university students are choosing to study in Copenhagen than ever before, which means that many young, smiling faces are eagerly taking part in Danish culture, at least for a semester. Their experiences will be formative, and they'll doubtless return with to the USA with positive views of Denmark and its people. As for the readers of

Church and Life . . .

we, too, have positive to work to do.

Gifts to Church and Life

Sustainers (more than $ 50)

Anita Clark

Donald Wegener